Appleby’s Carlos de Serpa Pimentel and Esmond Brown acted for the attorney of the settlor’s Islamic law heirs.

This article, written by Elizabeth Doherty and Charles Gothard of Macfarlanes LLP in London (who advise the trustee), explains the case and provides commentary on the practical approach the Cayman Court (Court) is willing to take in a complex situation, in particular one with limited scope to consult beneficiaries, provided that a trustee has done its homework in making appropriate enquiries in the exercise of its discretionary dispositive powers. It also includes a “Counsel’s Footnote” from Andrew De La Rosa (as Counsel for the trustee), which considers the case in the wider context of Shari’a forced heirship and succession planning.

Click here for a downloadable copy from Macfarlanes or read below for a full breakdown of the matter.

The Trust

The applicant (AA) made the application in its capacity as the corporate trustee of a discretionary trust, governed by the laws of the Cayman Islands (the Trustee and the Trust). The Trustee is managed and administered by Saffery Champness in Guernsey.

The settlor of the Trust, whose personal assets were applied in funding the Trust’s substantial investments, was a very wealthy member of a Middle Eastern Arab Muslim family (the Settlor). He wished to establish a trust structure to hold and administer assets he intended to acquire in future, and which ultimately came to include an eclectic range of valuable investments. On the basis of Cayman Islands professional advice obtained prior to the creation of the Trust, a Cayman Islands law-based structure was proposed in which the principal holding vehicle would be a discretionary trust.

That advice, which was followed after detailed consideration, led to the discretionary beneficial class of the Trust being defined in potentially very wide terms, as part of an exercise in preserving a degree of flexibility for the Settlor, consistent with his general wishes. The class included the Settlor (described in the Trust deed as the “Principal Beneficiary”), his children and remoter issue, and the spouses of the Settlor and his children and remoter issue (including widows and widowers), as well as any person validly added by the Trustee during the Settlor’s lifetime (a power which the Trustee had not exercised prior to his death).

All members of the Settlor’s family within the discretionary beneficial class are Muslims. The Settlor himself was a devout Muslim and was educated in and familiar with the Islamic law principles applied in his and his family’s home country, including in particular, those governing inheritance.

In recognition of those principles, and notwithstanding the wide definition of the beneficial class, the Settlor had, from the inception of the Trust in 1990 to shortly before his death, expressed a consistent wish (verbally and in various letters of wishes) that, following his death, the Trust assets be distributed to his “Heirs” as identified by the Islamic law of inheritance applied in their home country. In addition, the Settlor supplemented his original letter of wishes with additional requests that after his death, the Trust assets be distributed among his Heirs as soon as practicable and

the Trust be wound up. This derived from the Settlor’s own experience of delays in the distribution and wind up of relatives’ estates under Shari’a law procedures.

While the Heirs (limited by Islamic law to his wife and adult children) were all certainly within the beneficial class of the Trust, they only represented a very small proportion of the potential beneficiaries in existence at the time of the Settlor’s death. Indeed, by that time, a huge number of potential

beneficiaries existed, including many minors.

The value of the assets comprised in the Trust was substantial and the estimated value of the Settlor’s free estate, which was to pass to Heirs, was even larger. Of further relevance, the evidence recorded that there was no

dispute or doubt that the Settlor’s family as a whole already held significant wealth, apart from the assets comprised in the Trust and the Settlor’s free estate.

The Trustee’s inquiries

In considering whether or not to exercise its discretionary powers to liquidate and then distribute the entire Trust fund to the Heirs alone (to the exclusion of all others within the discretionary beneficial class) and subsequently to wind up the Trust (what became, the “Proposal”), the Trustee undertook a thorough investigation into: (i) the creation and drafting of the terms of the Trust and its subsequent administration; (ii) the history and significance of the Settlor’s wishes; (iii) the number and identities of the members of the Settlor’s family who fell within the beneficial class; and (iv) the significance of Shari’a law and the Muslim faith and teachings to the Settlor and his family.

In so doing, the Trustee consulted the following parties.

- BB, the first defendant, appointed to represent the interests of the Heirs in the application. BB had many years’ experience of acting in the Settlor’s affairs and as an intermediary between him and members of his family in financial matters. Significantly, he had been directly involved in the creation of the Trust and its subsequent administration. Following the Settlor’s death, he had also been appointed by the Heirs as their attorney, and in such role had been given global authority to represent and act on their behalf in all matters relating to the distribution of the Settlor’s assets amongst them.

- The Heirs themselves. Lisa Vizia (the lead Trustee director, who had been personally engaged in the administration of the Trust since 2002) arranged individual meetings with each of the Heirs and presented the Heirs with, and asked them or their representatives to confirm the accuracy of, detailed statements of the identities of the members of each of their own families.

- Two of the principal draftsmen of the Trust.

- A foreign legal practitioner qualified in the applicable Shari’a law, London solicitors (Macfarlanes LLP) and Cayman Islands counsel experienced in creating and administering trusts for Muslim Arab clients.

Practical limits to the Trustee’s inquiries

The Trustee faced various serious hurdles in carrying out its investigations. For example, it became clear that publicly available information on the Settlor and his family was, in important respects, inaccurate and incomplete. Further, the inquiries that the Trustee was able to complete disclosed not only that the discretionary beneficial class was very substantial, but that almost half were minors.

It also became clear to the Trustee that, given the strict religious and cultural traditions that the Heirs and their families lived by, inquiring into the individual financial circumstances of the Heirs and their families was not only impractical but would raise a considerable risk of putting the Trustee in an invidious position. In particular, BB, with his long experience of dealing with members of the Settlor’s family, gave evidence that it would simply not be regarded as appropriate by family members for the Trustee to make inquiries into their personal finances. Therefore, even if such inquiries were theoretically possible, requiring information as to personal circumstances and wishes would likely be considered as an affront, and damaging to the Trustee/beneficiary relationship.

The application

Given the momentous nature of the Proposal (and particularly as detailed inquiry into the individual circumstances of the majority of the beneficiaries was not deemed possible), the Trustee sought the approval of the Court (under the inherent jurisdiction and section 48 of the Trusts Law (2018 Revision)) to the Proposal.

In so doing, it joined BB as first defendant in his capacity as attorney to the Heirs and Cayman Islands attorney Colin Shaw of Colin Shaw & Co as amicus curiae to represent the interests of the non-Heir beneficiaries. The Trustee proposed Mr Shaw’s appointment as amicus curiae in order to put before the Court any considerations thought relevant to the position of the non-Heir beneficiaries. The Trustee considered this important because no non-Heir beneficiary was, as a practical matter, in a position to fulfil that role.

The Trustee had previously made a confidentiality application, which included, inter alia, an order that the originating summons be anonymised.

The law

In relation to confidentiality, the Court granted the order requested, including the anonymisation order, being satisfied, in accordance with the guidance given in Julius Baer Trust Co v AB3, that in this case the disclosure of the identities of the parties would be harmful to the interests of the beneficiaries while anonymisation would not impede

public access to open justice.

In relation to the substance of the application, it was common ground that in “Category 2” Public Trustee v Cooper applications (where a trustee is not surrendering its discretion but seeks the sanction of the court for a “particularly momentous” decision), the questions for the Court will normally be:

- does the trustee have power to enter into the proposed transactions?

- is the Court satisfied that the trustee has genuinely formed the view that the proposed transactions are in the interests of the trust and its beneficiaries?

- is the Court satisfied that this is a view that a reasonable trustee could properly have arrived at?

- has the trustee any conflict of interest, and if so, does the Court consider that the conflict prevents it from approving the trustee’s decision.

Three out of these four criteria were ultimately accepted by the parties not to be the subject of any significant dispute. In relation to criterion (1), the dispositive provisions of the Trust were unquestionably wide enough to enable the Trustee to carry into effect the Proposal and pay or apply the Trust fund to or for the benefit of some members of the beneficial class to the exclusion of the other members. There was also no issue between the parties as to criteria (2) or (4) or as respects the momentous nature of the Proposal.

The focus of the CJ’s attention was therefore on criterion (3) and whether, having regard to the second question posed by Lord Walker in Pitt v Holt4, the Trustee had made an error in failing to give proper consideration to matters relevant to the making of a decision that was within the scope of their dispositive powers and had thus carried out “inadequate deliberation”. In the circumstances of this case, the question for the CJ was therefore whether, in the exercise of its discretionary powers to carry out the Proposal, the Trustee was obliged as part of its duty of adequate deliberation to inquire into and consider the circumstances of each and every member of the wider class of beneficiaries with a view to benefiting them or whether it could reasonably decide to benefit only the Heirs, without any further inquiry or consideration.

The CJ correctly identified that, in considering criterion (3), the Court’s function was to apply the “rationality standard”. As such, “once it appears that the proposed exercise is within the terms of the power, the Court is concerned with limits of rationality and honesty; it does not withhold approval merely because it would not itself have exercised the power in the way proposed”5.

The decision

In giving his approval to the Proposal, the CJ commented:

“I am satisfied that the Trustee has arrived at not simply a rational decision but one which follows very careful deliberation and inquiry and, as [Carlos] de Serpa Pimentel [of Appleby (Cayman), for BB] said, an approach which may be described as a “text book” approach to the issues. I do not think, [as has been proposed by my amicus] that it would be appropriate for me to second guess the Trustee’s exercise of its discretion, which it indisputably has, by way of directing further inquiry (into the circumstances of the wider class of beneficiaries).”

He was not persuaded that it could be considered practical to notify, and seek individual views from, all adult non-Heir beneficiaries (and therefore not seeking to do so was not irrational). In particular the CJ accepted the submissions from Andrew De La Rosa, as counsel for the Trustee, and the evidence on behalf of the Trustee and from BB that he referred to, that it would put the Trustee in an invidious position and damage the Trustee/beneficiary relationship if it was forced to make intrusive inquiries of the beneficiaries, in particular given the religious and cultural traditional context in which the family operated. In any event, the CJ accepted the Trustee’s evidence that it was satisfied that the non-Heir beneficiaries of the Trust would, in due course, stand to benefit from the same Islamic laws of inheritance that the Settlor and his Heirs benefited from and that, given the extent of the Settlor’s and the Heirs’ wealth, there would in any event be substantial financial provision to all members of the discretionary beneficial class. As such, the Trustee was right not to be concerned to ensure that direct financial provision for the non-Heir beneficiaries was made from the Trust.

The CJ noted that in identifying and considering members of the beneficial class and their views the Trustee was not obliged to “survey the world from China to Peru” (to quote Harman J in Re Gestetner Settlement6), but had, in

fact, effectively done the equivalent of such a survey by conducting the thorough investigations summarised above.

The CJ was entirely satisfied that the Trustee had “done its homework” and undertaken proper inquiries in deciding to implement the Proposal. He considered the Proposal itself was “well within the bounds of rationality” and no-one could seek to characterise the decision of the Trustee as capricious or irresponsible. It was clear to him that the wide ambit of the term “beneficiary” in the Trust deed was simply intended to afford the Settlor flexibility during his lifetime and did not contradict his clear and consistent wish that only his Heirs should benefit.

Further analysis

The practical and flexible approach taken by the Court should provide comfort to the well-prepared trustee facing a momentous decision in complex circumstances.

The CJ was clearly assisted in his decision by the careful and detailed evidence and submissions given by the Trustee and BB. He was complimentary of the thorough approach the Trustee took to legal analysis and factual investigation, to the formulation of the Proposal on commercial terms and to the Court application itself. He was also appreciative of the assistance provided by the amicus in ensuring he was presented with all arguments for and against the blessing of the Proposal.

Although the Trustee was described in the written reasons as taking a “textbook” approach to the issues, this case may in fact be better seen as an example of a trustee looking beyond the textbook in order to ensure the proper exercise of its powers in a situation where novel circumstances meant it was not able to take the conventional approach of detailed inquiry and extensive consultation amongst all ascertained beneficiaries.

This was an unusual case, both in terms of the sheer size of the Trust fund and the identity, number and religious and cultural sensitivities of the beneficiaries. The approach necessarily taken by the Trustee here will not – with a different fact pattern – always be appropriate and it will, of course, always remain best practice for trustees, in their deliberations, to consult with their beneficiaries in order to ascertain their wishes and needs. In any event, trustees should expect courts to analyse its decision-making in minute detail and conduct and record their deliberations (and, indeed, prepare their evidence) with that in mind.

For the Trustee: Macfarlanes LLP (London), Andrew De La Rosa of ICT Chambers (Cayman) and Bedell Cristin (Cayman)

For BB: Carlos de Serpa Pimentel of Appleby (Cayman)

As amicus: Colin Shaw of Colin Shaw & Co (Cayman)

Heard & judgment delivered: 11 October 2019

Written reasons delivered: 14 February 2020

1FSD CAUSE NO. 137 of 2019 (ASCJ)

2[2001] WTLR 901

3[2018 (2) CILR 1]

4[2013] 2 AC 108, at 135 [60-61]

5Lewin on Trusts (19th Ed) at section 27-079-080

6[1953] Ch. 672

Counsel’s footnote

Provided by Andrew De La Rosa of ICT Chambers (Cayman)

Some wider context

The great divide between forced heirship systems and the common law approach to freedom of disposition by will or lifetime gift is seldom considered in reported cases. Why that is so is something touched on briefly below, but there is no doubt that AA v BB is an example of a trustee successfully navigating some inherent and fundamental difficulties that divide creates.

Given the very substantial number of “legacy” and newer trust structures which, practically inevitably, will confront similar issues, the decision is a very important guidepost in what is something of a minefield for professional fiduciaries. The problems are not confined to the trust context but extend to rules concerning the interests, rights and liabilities of various parties in cross-border estate administrations. This was also a feature of the background to AA v BB but the focus here is on the trust dimension.

In this case, the forced heirship system in question was that based on Islamic law principles – the Shari’a law system. It would be difficult to overstate the impact of the Shari’a inheritance rules on family business succession planning and wealth management structuring where those rules are potentially engaged. Textbook, academic and learned periodical discussions about forced heirship, trusts and other western secular law-based fiduciary structures are often focused on their interaction with European civil code rules. But the Shari’a rules are potentially applicable to vast numbers of people in many of the established and emerging wealth creation centres.

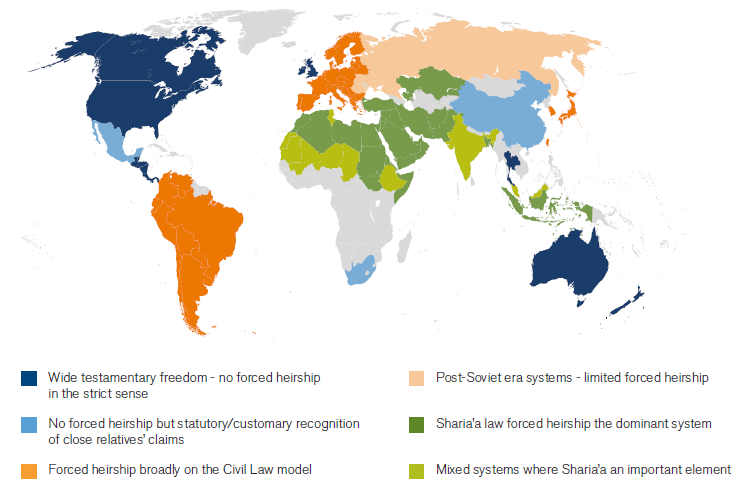

To put this in a global context, this graphic attempts to illustrate the geographic spread of the main present-day inheritance systems. It will be immediately apparent that in most countries, forced heirship of some kind is the rule and that the Shari’a systems are relevant well outside their origins in the Middle East, either as the prevailing system or one of those given effect to by local law.

Principal inheritance systems – forced heirship and others

Specifics of this case

In AA v BB, the system engaged was of the majority Sunni school of Islamic jurisprudence. The Settlor was steeped in that system and wished to honor what he, in common with many settlors of Muslim descent, regarded as fundamental religious obligations. Amongst other things the evidence established that he knew who his Heirs would be in terms of closeness of family relationship to him. To this might be added a general observation. Experience teaches that the certainty of entitlement to a share in an estate, however exactly it is calculated, is often the most important feature of Islamic and other forced heirship systems so far as successors to the deceased are concerned.

However, the Settlor also wished, as many if not most settlors do (whatever their cultural background), to create a secure but flexible asset management structure over which he could retain a significant measure of lifetime control. His ultimate dispositive intentions reflected what experience also teaches is very frequently the case in Muslim families with significant and established wealth, which is that on the death of the founder, such wealth should devolve on the founder’s Shari’a law heirs in the specific shares the Shari’a law prescribes.

The Settlor made this intention clear when the Trust was established. Thereafter, the Trustee regularly, and rightly, asked the Settlor to confirm whether or not that intention had changed. The Settlor’s responses, coupled with his deathbed reiteration of them, provided a kind of foundation stone on which the Trustee’s eventual Public Trustee v Cooper application could be partly based.

The specific context was a Cayman Islands law-based structure administered from Guernsey. It is worth noting that these two (as well as other) established trust jurisdictions have what is commonly described as “anti-forced heirship” legislation, intended to protect trusts and other structures from foreign law forced heirship claims. There is a superficial inconsistency between that protection and asking the court of such a jurisdiction to sanction a disposition that gives effect to foreign forced heirship rules. That view, however, really misses a basic point.

Legislation of this kind is perhaps better understood as “anti-foreign law” in its true scope but even that slightly obscures its underlying practical effect, which is to afford settlors a high degree of freedom to structure assets in what they conceive is in their own and their successors’ best interests. In a sense, the flip side of the anti-forced heirship coin is the freedom to cater for forced heirship entitlements, and the expectations and inter-generational obligations they create, if the settlor wishes to do so. This was of the essence in the present case.

The Cayman Court’s decision is consistent with this. It is beyond doubt that the Cayman Islands’ own legislation against foreign law claims, and that of other jurisdictions which have largely adopted the Cayman Islands statutory model, can be accounted a substantial practical success in deterring forced heirship claims in many trusts’ home jurisdictions. A settlor’s clearly expressed dispositive intentions are, however, never to be disregarded and in this case were ultimately carried into effect.